À propos de nous

Shenzhen Lunfeng Technology Co., Ltd

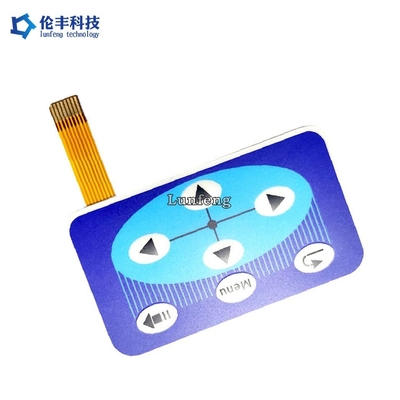

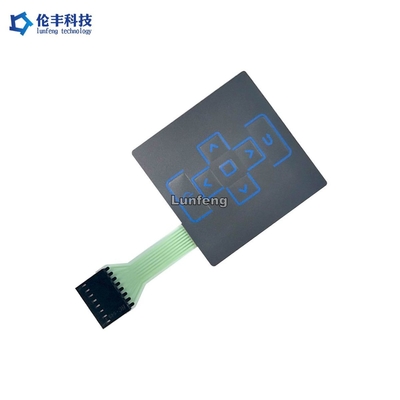

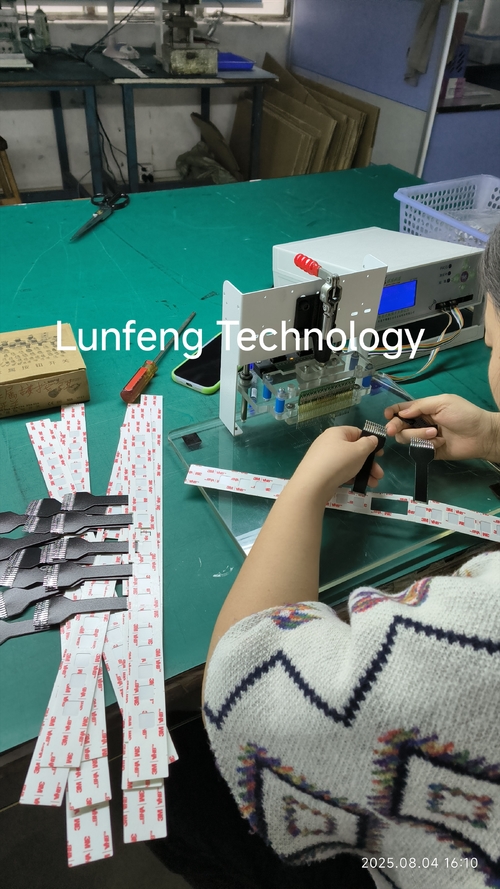

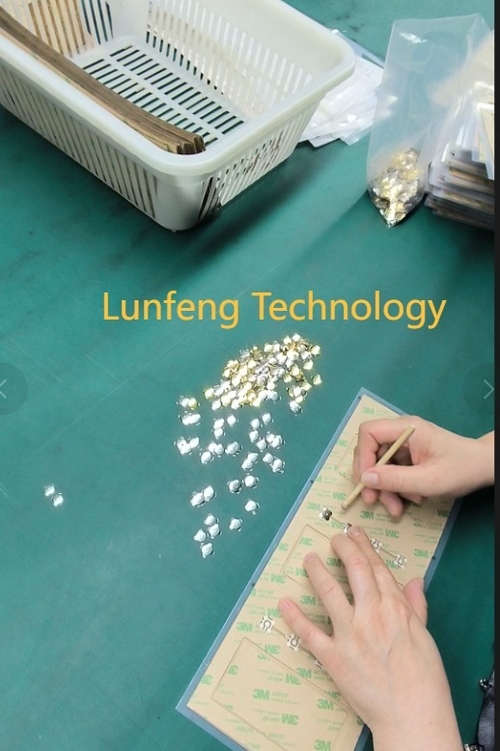

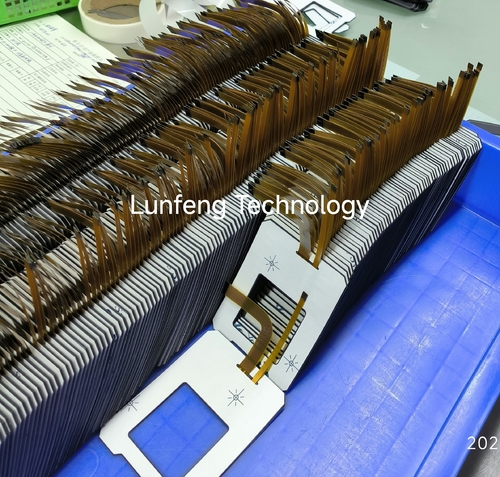

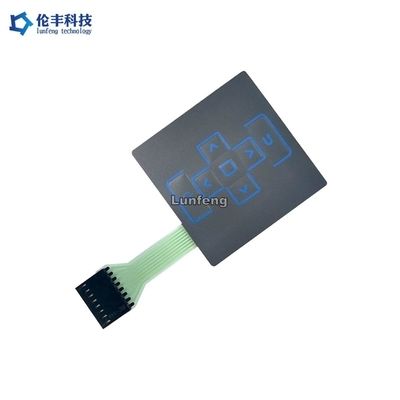

La société Shenzhen Lunfeng Technology Co., Ltd. (en anglais seulement)C' était...créée en 1995, principalement engagée dans la conception, la production, la vente et le service de toutes sortes d'interrupteurs à membrane, de revêtements à membrane, de revêtements graphiques, de plaques PC, PVC, PET et aluminium, de lentilles acryliques, de plaques d'identification métalliques,panneau d'écran tactile, époxy cristallin, papiers d'étiquette et matériaux composites thermodurcissables pour pressage ...